In conflict zones far from the eyes of the world it is the wounded and the sick that struggle to survive. But as the lines between aid workers and military become blurred, as NGOs are increasingly attacked, the rules that protect the innocent and injured are breaking down. The confused relations between military and NGOs introduce ever more suffering into the hell that is war. An intelligent and fascinating insight into the politics of war zone aid.

"Half an hour ago there was a car-jacking. The driver was shot and the two expatriates were kidnapped" Vittorio Oppizzi from MSF in Daadab, Somalia tells us, describing one of the terrible incidents that have become all too common. As a result of the kidnapping, they are forced to reduce the team as a security measure and most will be evacuated. The team realise the need for evacuation, but on an emotional level they know what they are leaving behind in terms of their lifesaving work.

"It's very difficult for a lot of these individuals to just pack up one day, leave, and know that behind there's not going to be much provision."

Since the turn of the millennium aid workers are finding themselves increasingly under threat. The last decade has been the deadliest on record for humanitarians with more than 200 national and international aid workers killed. And it's not just a matter of getting caught in the crossfire; humanitarian aid workers are sometimes deliberately targeted. They are often confused with other military-run aid agencies, which do not always have a neutral stand in the conflict.

This has impacted heavily on their ability to provide life-saving support to the civilians who are forced to experience the horrific consequences of conflict violence: having to flee their homes, being shot, bombed, maimed, raped, tortured and murdered. As infrastructure and health services collapse, these people's chance of survival are dramatically reduced.

The Helmand province in Afghanistan is one of the most difficult areas to reach victims. Doctors here are sometimes kidnapped, killed or face political actions for helping the wounded. Aid organisations are often caught in the crossfire between competing forces in the region.

"Every single day we see people having to make very tough choices between the different sides. They will receive a night visit from an opposition group, the next day they will have to account to the official Afghan forces or international forces," Pierre Krahenbuhl, director of operations for the Red Cross explains.

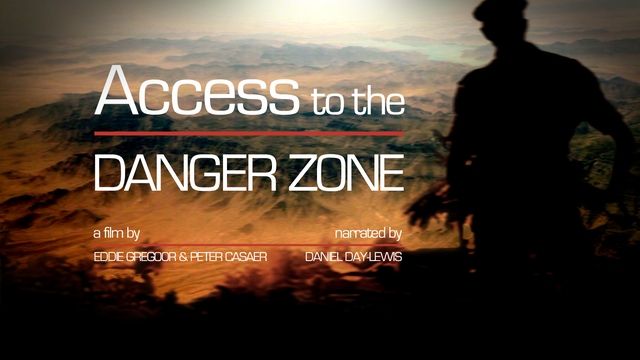

This stunningly shot film captures the extreme bravery and selflessness that aid workers display as they fight to save the innocent victims caught in the firing line. It reveals the increasingly fraught circumstances they work in and the unforgivably limited access they have to the people who need their help the most.

LEARN MORE.

WATCH MORE.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION.

In conflict zones far from the eyes of the world it is the wounded and the sick that struggle to survive. But as the lines between aid workers and military become blurred, as NGOs are increasingly attacked, the rules that protect the innocent and injured are breaking down. The confused relations between military and NGOs introduce ever more suffering into the hell that is war. An intelligent and fascinating insight into the politics of war zone aid.

In conflict zones far from the eyes of the world it is the wounded and the sick that struggle to survive. But as the lines between aid workers and military become blurred, as NGOs are increasingly attacked, the rules that protect the innocent and injured are breaking down. The confused relations between military and NGOs introduce ever more suffering into the hell that is war. An intelligent and fascinating insight into the politics of war zone aid.