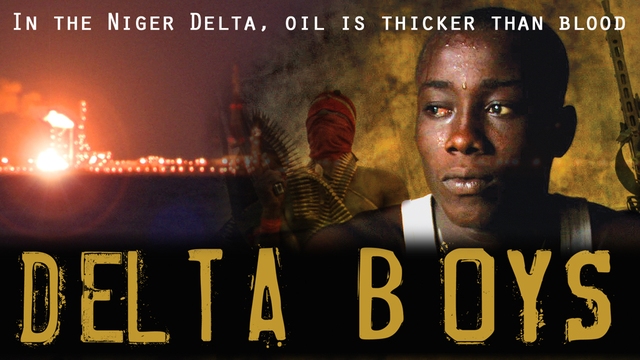

Ateke Tom, the "Godfather" of the Delta Vigilante Force, and his men attack oil pipelines, kidnap foreigners and make the Niger Delta region a no-go zone. It's all in a bid for a share of government wealth in this oil-rich region. Meanwhile, in a village caught in the crossfire, 22-year-old Mama struggles to give birth while militants launch raids from across the river. Through close and compelling stories this doc gives a human face to a struggle for survival.

Tension hangs heavy over the Delta. Government forces control the creeks in gunboats. Gunfire crackles overhead. At the first camp we visit we get a hostile reception. The white man isn't welcome here. At

"Camp Angola 3" we meet Ateke Tom, a militia leader who draws young men to the fight with the promise of alcohol, cigarettes and a square meal.

"I save people. That's why they call me Godfather" he claims. A one-time paid government thug, he cuts a brooding figure. Anger seethes just below the surface. Militia in tracksuit tops clean their weapons. Fights break out between them.

Chima found a father figure in Ateke Tom after his own father walked out. He and others sit guard at the camp's edge to stop those who

"don't like it here" trying to leave. But after falling asleep at their post they are whipped. Sobbing in the dirt, there is little honour left. The militia life is a lonely one, in which young men from different tribes are united only by anger.

"I have no friends here" says Chima.

Poverty is at the heart of this struggle. Cruising through the Delta, rainbows play on the surface of the oil-slicked water, as children in underpants run barefoot through dilapidated villages. Most people in this region of Nigeria, the eighth largest oil producer in the world, live on less than $1 a day. There are no good roads, good schools or good hospitals. When 23 year old Mama goes into labour, complications arise and the panic becomes deafening. Finally the plaintive cry of the baby wailing reminds us how tenuous life is here.

By contrast the nearby Mobil natural gas plant is lit up like something from another world. We are on reconnaissance with Okoloma Ikpangi militia at night, crouching low in the speedboat. They claim

"to fight for the less privileged" but villagers here have lost faith in them.

"It's a lie" whispers one,

"they are fighting for their own stomachs... If you say anything against them they will kill you". In nearby Bonny footage emerges of two fishermen executed for informing against the militia. Meanwhile villagers also cower in fear of army helicopter gunships. They fear the wrath of both sides.

Ateke Tom accepts a presidential amnesty with the promise of cash and development in the region. Posing for the camera before handing over a huge arsenal of weapons, the ceremony has a phoney feel, as surreal as the sight of militia men dancing in the bush in gas masks and bare feet. The amnesty sharply reduced unrest and led to a rebound in oil production, but will it last? Undoubtedly, many more weapons still remain in militia hands.

LEARN MORE.

WATCH MORE.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION.

Sundance Institute

Gucci Tribeca Fund

Ateke Tom, the "Godfather" of the Delta Vigilante Force, and his men attack oil pipelines, kidnap foreigners and make the Niger Delta region a no-go zone. It's all in a bid for a share of government wealth in this oil-rich region. Meanwhile, in a village caught in the crossfire, 22-year-old Mama struggles to give birth while militants launch raids from across the river. Through close and compelling stories this doc gives a human face to a struggle for survival.

Ateke Tom, the "Godfather" of the Delta Vigilante Force, and his men attack oil pipelines, kidnap foreigners and make the Niger Delta region a no-go zone. It's all in a bid for a share of government wealth in this oil-rich region. Meanwhile, in a village caught in the crossfire, 22-year-old Mama struggles to give birth while militants launch raids from across the river. Through close and compelling stories this doc gives a human face to a struggle for survival.

Sundance Institute

Sundance Institute

Gucci Tribeca Fund

Gucci Tribeca Fund