Prayer for Beslan

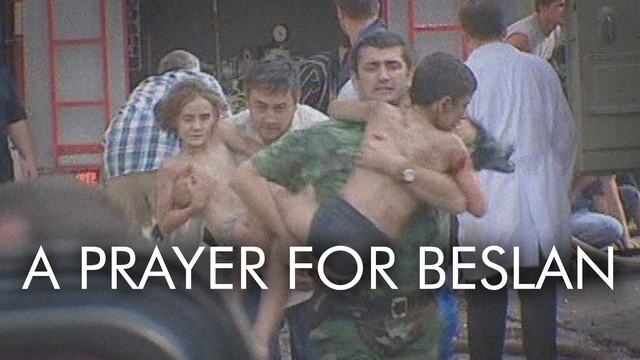

Beslan will forever be synonymous with the murder of hundreds of innocent children. One year on, how is the town coping?

Beslan will forever be synonymous with the murder of hundreds of innocent children. One year on, how is the town coping? Our documentary this week is a harrowing and powerful new film on the school siege and its enduring legacy. From the vilified headmistress to the bewildered local MP and grieving families, it depicts a once idyllic town now torn apart by anger. Includes an exclusive and candid interview with the main Russian negotiator.

Beslan will forever be synonymous with the murder of hundreds of innocent children. One year on, how is the town coping? Our documentary this week is a harrowing and powerful new film on the school siege and its enduring legacy. From the vilified headmistress to the bewildered local MP and grieving families, it depicts a once idyllic town now torn apart by anger. Includes an exclusive and candid interview with the main Russian negotiator.

September 1, 2004. Twelve year old Emma and her best friends Aza and Svetlana are looking forward to their first day back at school. "I followed them to school and watched them walk in," states Emma's mother, Irina. "They never came back." Days later, she would identify video footage of the girls huddled together in the school gym before the explosion. " When they found Emma, her body and head were totally carbonised."

Beslan is overcome by grief for its lost children. Hatred, anger and suspicion have permeated a community that was once so peaceful. "Why did they choose this small town of no importance? Why did they come here? They are hiding the truth," despairs mother Larisa Afanasova. In the absence of any real information from the government, the town has turned in on itself. "All the survivors are accused of something or another," states hostage Zalina Albegova. "The teachers are accused of saving themselves instead of the children."

Most of the town's hatred is targeted at School Number 1's headmistress, Lydia Tsalijeva. "As God is my witness I never wanted any of the children to be hurt," she declares. But it's in vain. "Principal - it's all your fault and we will kill you," reads the graffiti on the burnt out walls of her school. A bitter hate campaign has forced her from her job.

Paediatrician Dr Leonid Roshal led the negotiations to try and free the children. The hostage takers requested him specifically after he led the Moscow theatre siege negotiations two years earlier. "It took me three hours to get there. It might have been quicker if the government had provided me with a plane." Although the government insisted only 350 people were being held hostage, he knew immediately the situation was much worse. "I realised the number was much higher ... I kept changing the focus of the conversation, just to keep the negotiations going."

By the second day, the situation inside the school was appalling. Denied food or water, the children were weak and dehydrated. Some resorted to desperate measures. "It was terrible when the children went over to the buckets and started drinking their own urine," states Lydia Tsalijeva. "They soaked their white scarves and put them in their mouths, sucking all the moisture out of the velvet fabric."

Confusion remains over events leading to the siege's bloody end. But what motivated the hostage takers remains clear: ending the war in Chechnya. Until this is addressed, the lessons of Beslan will go unheeded. As politician Stanislav Kesayev puts it: "In time ahead, people will still have to live in fear. Because no one can guarantee that there will never be another Beslan."

FULL SYNOPSIS