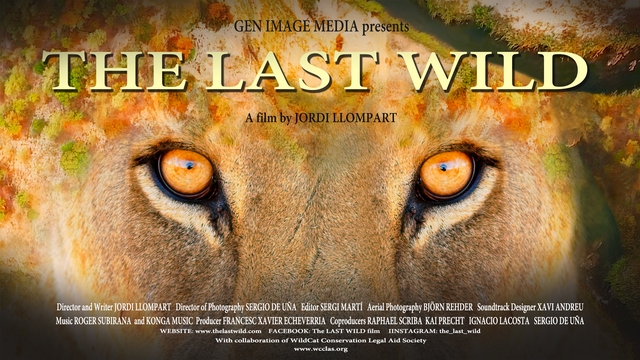

The Last Wild

Can we learn to share the planet we think we own?

In a man-made world hewn from nature, the exploitation of both living and inorganic resources is shaping the planet beyond recognition. For many animals, such human activity is gradually altering their land beyond habitable existence. Hunting in Africa for food, sport, and anger is drastically reducing animal populations. But there is still time to save and reconnect with nature. With governments protecting wild land, and through the Khoisan peoples' example of how to share life with other predatory animals, this ruminative doc explores how humans and animals might one day coexist in peace.

In a man-made world hewn from nature, the exploitation of both living and inorganic resources is shaping the planet beyond recognition. For many animals, such human activity is gradually altering their land beyond habitable existence. Hunting in Africa for food, sport, and anger is drastically reducing animal populations. But there is still time to save and reconnect with nature. With governments protecting wild land, and through the Khoisan peoples' example of how to share life with other predatory animals, this ruminative doc explores how humans and animals might one day coexist in peace.

"We never gaze at the stars or a tree without seeing ourselves, without seeing our reflection in them." Across Africa there is growing concern that our relationship with nature has become all take and no give. Our unsustainable, selfish opportunism is ruining what could be a far more beneficial co-existence.

We know that the ever-expanding boundaries of 'modern' civilisation are encroaching upon the wilderness of Africa. But there is also concern that major damage is being done by the continent’s more isolated communities. Donovan Darrington Prince, a wildlife guide, is frustrated: “I honestly don’t believe that people has respect for nature, animals or wildlife, especially in rural areas”.

Biological conservationists like Matt Claverley defend locals attacking wildlife: “if a wild animal is considered a threat to their children or livelihood, then of course their immediate need is for their family”. Yet this is not the whole story. Animals are also killed “to let off steam, because of contempt for animals or because of profit”. Poachers illegally sell horns, ivory and skins for easy money. They even hunt in land which governments have designated as nature reserves since the late nineteenth century. What’s more, poachers poison their carcasses. “The poachers often don’t want the vultures to give them away,” Ortwin Aschenborn elaborates, “so there is an active poisoning of vultures at the moment”.

“Technology has made people so impersonal and they are getting addicted to that,” thinks Christo Snyman, a wildlife writer and photographer. Our relationship with technology is blamed for ruining the miraculous bond with the wild that only a few tribes, like the Khoisan peoples of Southern African, retain today. Rather than killing lions, they prefer to talk to them in order to share some of their prey. “It will not kill the human being,” says Steve Kunta, a local wildlife guide. “They will move away and then a person can come and get the meat.”

Over the course of this passionate documentary, questions are raised over the capacity for larger mammals, like the elephant, to think like we do, even contemplate death. “They are very social animals, extremely like humans,” says Donovan. This meditative exploration of African ecosystems teaches us that if we learn to share our environments with the creatures we live amongst, there will be no need for the African plains to become the last wild.

FULL SYNOPSIS

We know that the ever-expanding boundaries of 'modern' civilisation are encroaching upon the wilderness of Africa. But there is also concern that major damage is being done by the continent’s more isolated communities. Donovan Darrington Prince, a wildlife guide, is frustrated: “I honestly don’t believe that people has respect for nature, animals or wildlife, especially in rural areas”.

Biological conservationists like Matt Claverley defend locals attacking wildlife: “if a wild animal is considered a threat to their children or livelihood, then of course their immediate need is for their family”. Yet this is not the whole story. Animals are also killed “to let off steam, because of contempt for animals or because of profit”. Poachers illegally sell horns, ivory and skins for easy money. They even hunt in land which governments have designated as nature reserves since the late nineteenth century. What’s more, poachers poison their carcasses. “The poachers often don’t want the vultures to give them away,” Ortwin Aschenborn elaborates, “so there is an active poisoning of vultures at the moment”.

“Technology has made people so impersonal and they are getting addicted to that,” thinks Christo Snyman, a wildlife writer and photographer. Our relationship with technology is blamed for ruining the miraculous bond with the wild that only a few tribes, like the Khoisan peoples of Southern African, retain today. Rather than killing lions, they prefer to talk to them in order to share some of their prey. “It will not kill the human being,” says Steve Kunta, a local wildlife guide. “They will move away and then a person can come and get the meat.”

Over the course of this passionate documentary, questions are raised over the capacity for larger mammals, like the elephant, to think like we do, even contemplate death. “They are very social animals, extremely like humans,” says Donovan. This meditative exploration of African ecosystems teaches us that if we learn to share our environments with the creatures we live amongst, there will be no need for the African plains to become the last wild.