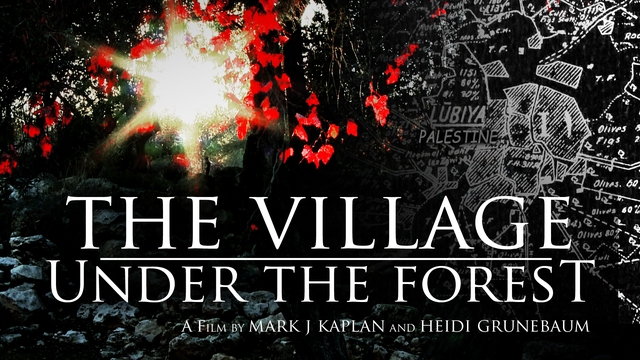

The Village Under the Forest

The real story of how the Palestinians were driven from Israel in '48

What happened in '48? It's the question that haunts the Israel/Palestine dynamic and defines so much of the conflict. This doc strips back the layers of myth, from denial to stories of mass genocide, telling the real story through the hidden remains of the destroyed Palestinian village of Lubya. Lying under a purposefully cultivated forest plantation, it holds many of the answers not only to the country's past, but also its future.

What happened in '48? It's the question that haunts the Israel/Palestine dynamic and defines so much of the conflict. This doc strips back the layers of myth, from denial to stories of mass genocide, telling the real story through the hidden remains of the destroyed Palestinian village of Lubya. Lying under a purposefully cultivated forest plantation, it holds many of the answers not only to the country's past, but also its future.

"Shh, if I don't tell, it didn't happen", a Jewish occupier of Palmach in the 40s says in rebuke to his wife who has suggested there are some things you don't talk about. At the end of his life, Motkele was determined to tell his story: "We knew that if you destroyed the roofs of their homes, the Arabs would leave. So a group of us guys destroyed the village roofs and they left. So easy, as if people's lives weren't involved." In doing so he raises that unspeakable topic in Israel, the destruction of Arab villages and driving of Arabs from the land. Palestinians call it 'The Nakba' or catastrophe. Israel make's it illegal to commemorate the event.

Heidi Grunebaum, a South African Jewish scholar and writer, leads us through the stories of Jews and Arabs who recount the story of '48 through the perspective of the Arab village of Lubya. She first came to Lubya as a student. She often visited the beautiful forest picnic spot nearby and knew nothing of the town's ruins lying under the forest floor. Jews from around the world had donated money to create the tranquil wooded hideaway.

But the stones on the forest floor tell the story of Lubya's Nakba and are not so easily silenced. "Whilst we were fleeing, I looked behind and saw Lubya in the distance, its houses were in flames." A Palestinian woman recounts. But an Israeli soldier from the time admits, "The Arabs of Lubya fled and I was ordered to destroy the houses quickly to prevent their return after the conquest. There were more than 1,000 houses."

But why did Israelis embark on this systematic destruction of Arab villages, even after Palestinians had fled? Simply, in the words of Israeli historian Ilan Pape, "They really didn't like the fact that the country still looked Arab, despite the fact the Arabs weren't there any more." What they wanted was to wipe out the memory of villages like Lubya. And how they went about it was by planting forests to hide the evidence. "One way they hid the existence of Palestinian villages was to plant recreational forests over the villages with European pine trees. Where the towns were large, you can see the new Jewish settlement and beside it a recreational pine forest."

But as the stories from both sides testify, it is not so easy to wipe the memory of whole towns, even in a country where commemoration of The Nakba is considered a crime. Through incredible rare archive and stories from both sides, this film provides a striking testament to why the Israel/Palestine divide remains so difficult to heal.

LEARN MORE.

"Shh, if I don't tell, it didn't happen", a Jewish occupier of Palmach in the 40s says in rebuke to his wife who has suggested there are some things you don't talk about. At the end of his life, Motkele was determined to tell his story: "We knew that if you destroyed the roofs of their homes, the Arabs would leave. So a group of us guys destroyed the village roofs and they left. So easy, as if people's lives weren't involved." In doing so he raises that unspeakable topic in Israel, the destruction of Arab villages and driving of Arabs from the land. Palestinians call it 'The Nakba' or catastrophe. Israel make's it illegal to commemorate the event.

Heidi Grunebaum, a South African Jewish scholar and writer, leads us through the stories of Jews and Arabs who recount the story of '48 through the perspective of the Arab village of Lubya. She first came to Lubya as a student. She often visited the beautiful forest picnic spot nearby and knew nothing of the town's ruins lying under the forest floor. Jews from around the world had donated money to create the tranquil wooded hideaway.

But the stones on the forest floor tell the story of Lubya's Nakba and are not so easily silenced. "Whilst we were fleeing, I looked behind and saw Lubya in the distance, its houses were in flames." A Palestinian woman recounts. But an Israeli soldier from the time admits, "The Arabs of Lubya fled and I was ordered to destroy the houses quickly to prevent their return after the conquest. There were more than 1,000 houses."

But why did Israelis embark on this systematic destruction of Arab villages, even after Palestinians had fled? Simply, in the words of Israeli historian Ilan Pape, "They really didn't like the fact that the country still looked Arab, despite the fact the Arabs weren't there any more." What they wanted was to wipe out the memory of villages like Lubya. And how they went about it was by planting forests to hide the evidence. "One way they hid the existence of Palestinian villages was to plant recreational forests over the villages with European pine trees. Where the towns were large, you can see the new Jewish settlement and beside it a recreational pine forest."

But as the stories from both sides testify, it is not so easy to wipe the memory of whole towns, even in a country where commemoration of The Nakba is considered a crime. Through incredible rare archive and stories from both sides, this film provides a striking testament to why the Israel/Palestine divide remains so difficult to heal.

LEARN MORE.

WATCH MORE.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION.