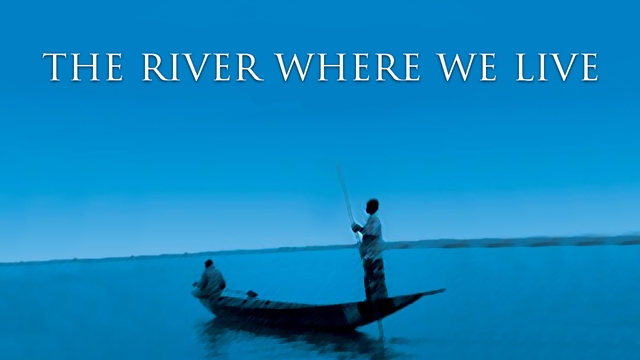

The River Where We Live

Far from the murderous fighting that ravages many African countries, people from diverse ethnic groups live together peacefully along the Niger river

Far from the murderous fighting that ravages many African countries, people from diverse ethnic groups live together peacefully along the Niger river. But increasing drought threatens to destroy their traditional lifestyles. Refreshingly free from sensationalism, The River Where We Live makes us feel for the canoe maker, the captain of the ship, the fishmonger and the fisherman, as if they were old friends.

Far from the murderous fighting that ravages many African countries, people from diverse ethnic groups live together peacefully along the Niger river. But increasing drought threatens to destroy their traditional lifestyles. Refreshingly free from sensationalism, The River Where We Live makes us feel for the canoe maker, the captain of the ship, the fishmonger and the fisherman, as if they were old friends.

"I've been practicing this craft since 1954" , says the canoe-maker "now my children have come to learn". He stands proudly on his canoe against the endlessly blue horizon, a postcard of Africa, with its promise of exploration and nature. But like Africa, the canoe-maker's relationship with the river runs deeper than the beautiful image. "A perfect balance between the height of the canoe and the river is essential" he carefully instructs his son. But water levels are lowering and"there's no longer any fortune in this work, only respect and consideration" he sadly admits. Like the rest of the Niger's people, the canoe-maker views the river as a constant provider - a source of power, wealth, food and beauty. Looking at him now staring into the blue horizon, he seems to be watching the river die before his eyes.

"I started working on the boats as an apprentice" says the Captain. Here, trades are handed down from generation to generation and the young are honoured to continue this work around the river."Now I have my own apprentice" the captain says proudly gesturing to Goumeysia who eagerly watches the waves. He is learning how to distinguish between shallow and deep water. "Navigating high waters is like driving on a paved highway" the captain says smiling. But now that the water levels are dropping, "life is harder" he admits.

"I've been a fishmonger for 43 years" says a friendly, brightly-dressed woman in the market. "Mopti used to be a pleasant place. You could find what you wanted to eat and no one would argue." Now most of the saleswomen she learned her trade with have disappeared and arguments over supplies of ice and fish prices, are rife. "The water shortage has made many breeds of fish disappear" she explains "we keep having to go further, which cuts into our profits".

Back at the river, nets are reeled in with nimble hands. "I don't know any other kind of work" says the fisherman. His parents made a fortune out of the fishing trade. But now "when you bring fish to Mopti, you're at the mercy of the middlemen. There are no profits to be made from fish". Yet he will never abandon his work or the river, which has nourished his family for so long. "The children are more accustomed to this way of life" he says "the minute we leave for the misery and squalor of the city, they feel unwell".

Yet the floods come less often and the dry season lasts longer. Shepherds must roam further and further for food for their cattle. Fishmongers must search wider for fish to sell. "We come together. We complete each other in work and spirit" says the fisherman, speaking of the diverse communities living around the Niger river. But as he looks at his son lying happily on a canoe, trailing his fingers in the blue water, it seems as if he is speaking about the river itself.

FULL SYNOPSIS