The Producers

Jenni Kivistö - Director/Writer/Editor

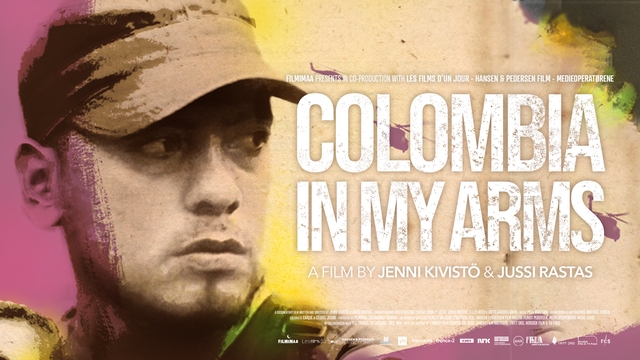

Jenni Kivistö is a documentary director who has lived and studied in Colombia for 6 years before moving back to Finland. She graduated from the Black Maria film school in 2013, and is currently studying Documentary Film master programme in Aalto University. Her short film Äiti (Mother, 2016) was awarded the Silver Mikeldi Documentary at ZINEBI and has been screened at mayor festivals like Clermont-Ferrand and Cairo International Film Festival. Her first feature-length documentary, Land Within (2016), had its world premiere at DOK Leipzig in 2016 as part of the Next Masters competition series.

Jussi Rastas - Director/Writer/Editor

Jussi Rastas is a Finnish documentarist who has lived 4 years in South America, in Colombia, Peru and Chile, and studied cinematography in Spain (ESCAC, Escola Superior de Cinema i Audiovisuals de Catalunya). He has filmed and produced a feature documentary Knucklebonehead (2013, screened at Gothenburg IFF, DocPoint, Helsinki IFF, DocsDF), a co-production with the Finnish Broadcasting Company Yle. In recent years, Jussi has directed and filmed several documentary short films and worked as a director and cinematographer for the Red Cross in conflict zones in Ukraine, Syria and Africa.

Making The Film

Director's Statement

Although we have both lived in Colombia and South America for years, we have never thought to make a film about the Colombian conflict. Initially, as foreigners, we didn’t have a personal connection to this immense topic. However, because of our personal backgrounds in Latin America we happened to be in Colombia around the time of the peace agreement being signed between the FARC guerrillas and the Colombian Government.

The country seemed to be breathing a hope — maybe for the first time in its recent history. Suddenly, we were offered an opportunity to film in a guerrilla camp, which became possible due to this historic event. Taking this chance would lead to us to work in Colombia for a year and half, on an extensive film related to the conflict.

The original idea was to make a beautiful and calm poetic documentary about peace, reflecting the capacity of human beings to coexist and share a country after decades of armed conflict. However, soon the atmosphere in Colombia both in the rural areas and cities started to intensify. There was a clear opposition to the peace accord and you could see actions taking place that were anything but peaceful.

As uncertainty, fear and confusion rose all over the country and as the people we were filming began to face challenges, we felt it important to start following the escalating societal situation. The much-celebrated peace did not seem so apparent anymore. We understood the reality at hand was much more complex than we had originally thought and many of our preconceptions had been proven wrong.

Already in the beginning we decided to create a polyphonic documentary that would listen to several characters’ opinions from across Colombian society. In looking for characters and a balance for the documentary we assessed who seemed to be the protagonists of the current circumstances.

Eventually, after an organic process of extensive work, good contacts and lucky coincidences we found ourselves close to people who opposed each other, yet were very open to discuss difficult matters with foreign filmmakers. We were seen as neutral, as we were not part of the conflict. This was an opportunity to open windows for the audience to better understand the diverse realities that gave rise to this chaotic situation.

When forming the first ideas about the film we ran into an article about Wetiko. According to a native American tribe the Europeans — the colonizers of the continent they claimed to have discovered — suffered from a disease called Wetiko. This disease made its carrier think that abusing other human beings’ vital energy was a reasonable way to live. This became one of the main leads for this documentary. To what extent are the current human societies possessed by Wetiko?

As the American continent has been remarkably established in an oppressive relationship, we wanted to examine the new Colombian context and ask if the mindset could change and whether people might finally find ways to live in peace after decades and centuries of abuse. Regarding the current conflict, both the state and the guerrillas could be accused of being abusive in many different ways. If the peace accord was about to be the ground-zero for a new era, would people continue to be abusive to one another?

With this film we’re not trying to explain the Colombian armed conflict. Through the eyes of distinct Colombians we observe how civilization is built, if peace can be possible in a polarized society and if not, then why not? It was clear we didn’t want to make propaganda for any group or political party, but to provide an unbiased view examining the situation from humane perspectives, leaning to change, towards non-violent actions and peaceful coexistence.

In the film we attempt to remain as true as possible to the things we personally witnessed. All the characters and all the events in the film are real, and there is no fictional element in this film: no actors, no fictitious or acted scenes, no planned dialogue. We filmed in Colombia for a year and half and immersed ourselves in the subject, making sure we had a profound view of the situation. The facts presented in the film have been evaluated to be truthful by Colombian experts and independent studies.

We think that local people should be equipped to tell their own stories and create their own works about the topics addressed. However, in this particular case we believe that as Europeans we have been able to access certain circles that are inaccessible to Colombians themselves. In addition, a Colombian filmmaker could put her or himself into great danger when dealing with a political subject. Only during the production of this film, 412 Colombian human rights defenders were murdered — in addition to them, one Colombian filmmaker and four journalists working in rural areas were killed in this post-peace accord era.

Aesthetically we wanted to make high quality cinema that would speak to the audience at all cinematic levels. The extensive time we spent in Colombia allowed us to refine the aspect of visual storytelling. Each image and element in the film has a significance, a symbolic value that adds to the story while creating the desired style and artistic qualities we were searching for. While filming we were intrigued to think of how García Márquez’ magical realism would be presented in a cinematic form.

We felt a need to create a film that would be equally valid for the international and Colombian audiences. In the editing this was a challenge, as well as forming a multi character intertwining narration that would provide sufficient information to understand the context, but not reducing the drama. We also had to acknowledge that we couldn’t avoid the film being taken politically although our filmmakers’ point of view was entirely humane. It took almost a year to achieve the correct balance during the editing phase.

Eventually, the film ended up being a very heavy documentary that deals with inequality, power and colonialism via both tragic and comic forms. The film portrays individuals who wish the best for their country, but are able to find justification for war under certain circumstances. The film lets the spectator approach distant bubbles that in an optimal world would understand each and achieve a lasting peace.

Although the film takes place in Colombia, we believe it deals with universal topics, closely observing the contemporary condition of humanity within the current global context. Our aim with the film is to make visible societal and human characteristics, some of which are counterproductive for humanity, while others keep us together regardless of our dissenting opinions. We hope the film can raise constructive discussion for bringing realities closer to each other.

Colombia's much-celebrated peace agreement runs the nation into chaos. FARC guerrilla Ernesto, poverty-stricken coca farmers, a mysterious aristocrat, and a passionate right-wing politician struggle at the edge of their morals as they reach for contradictory dreams for a better Colombia. What happens to a very fragile peace in an unequal country, if doing the ‘wrong’ thing may easily be justified as the only viable means of struggle?

Colombia's much-celebrated peace agreement runs the nation into chaos. FARC guerrilla Ernesto, poverty-stricken coca farmers, a mysterious aristocrat, and a passionate right-wing politician struggle at the edge of their morals as they reach for contradictory dreams for a better Colombia. What happens to a very fragile peace in an unequal country, if doing the ‘wrong’ thing may easily be justified as the only viable means of struggle?

Festivals

Festivals

Göteborg Film Festival - Best Nordic Documentary Award Winner

Göteborg Film Festival - Best Nordic Documentary Award Winner

Helsinki Documentary Film Festival - Official Selection

Helsinki Documentary Film Festival - Official Selection

Thessaloniki Documentary Festival - Official Selection

Thessaloniki Documentary Festival - Official Selection

Films from the South - Winner - Best Documentary 2020

Films from the South - Winner - Best Documentary 2020

MOSTRA - Official Selection

MOSTRA - Official Selection

FICBC - Winner - Golden Owl for Best Feature Film

Reviews and More

FICBC - Winner - Golden Owl for Best Feature Film

Reviews and More